View Jane Addams Hull-House Museum in a larger map

Visit our Tour Destination: Illinois page to see the entire tour of the state’s

Save America’s Treasures sites.

|

| Jane Addams Hull-House Museum. Photo courtesy of Jane Addams Hull-House Museum. |

The University of Illinois at Chicago

800 S. Halsted

Website: Jane Addams Hull-House Museum

The Treasure: Hull-House

was America ’s

most famous settlement house—a place where the ideals of the Progressive Era

were put into practice, improving the lives of thousands.

Accessibility: The

museum is open Tuesday through Fridays from 10 to 4 and Sunday from noon to

4. It’s closed Mondays and Saturdays.

|

| Jane Addams. Image from Hull-House Yearbooks, courtesy of University of Illinois at Chicago Library. |

Background: Jane

Addams took the ideals of the Progressive Era and put them into practice.

Hull-House, a settlement house co-founded by Addams and Ellen Gates Starr in

1889, was her incubator. Through a wide array of programs and activities,

Addams and Starr endeavored to improve the lives of the residents of some of Chicago ’s poorest

neighborhoods. They fought for better urban living conditions, while

creating a safe environment where disadvantaged people could benefit from the

free offering of arts, culture, and education.

A reformist social movement that began in London in the middle of the 19th century, the settlement movement sought to bring

the upper class and the lower class together in environments of mutual

respect. Largely driven by the idealistic concerns of upper-middle-class

and upper-class women, the settlement movement was extremely flexible, ready to

engage in social work, cultural and art activities, recreational programs, and

education. Hull-House was not the first American settlement house, but

thanks to the drive of Addams and Starr it quickly became a beacon of the

movement in the United

States .

Known as “residents,” the volunteers who worked at

Hull-House offered a buzzing environment of classes, concerts, lectures,

theater, and training programs. They served a local community that was a

complex maze of small ethnic neighborhoods. Initially, they primarily worked with

Italians, Irish, Germans, Greeks, Bohemians, and Russian and Polish Jewish

immigrants. As immigration and migration patterns began to change the

makeup of the neighborhoods, Hull-House reached out to

Mexican-American and African-American families, as well. It was always the

working poor that were the focus of Hull-House—the people who worked long hours

as unskilled laborers at the garment industry sweatshops and the factories

along the Chicago River .

|

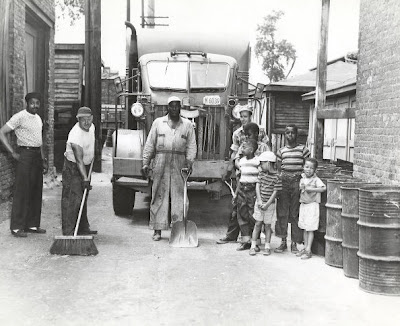

| At the Front Door of Hull House. Historic photo from Hull-House Yearbooks, courtesy of University of Illinois at Chicago Library. |

In the city’s poorest sections, sanitation was poor, wages

were low, and young children were recruited for some of the dirtiest and most

dangerous jobs. Hull-House was on the forefront of advocating for

improved government services and tougher industry regulations. Hull-House offered an oasis where families could imagine a better future.

Jane Addams wrote, “To feed the mind of the worker, to lift it above the

monotony of his task and connect it with the larger world, outside of his

immediate surroundings, has always been the object of art.” Following her vision, Addams organized and promoted art

classes and training programs to unleash creativity and tap latent talents.

Today, the Jane B. Addams Hull-House Museum

is an historic site that tells the story of America ’s most famous settlement

house. Exhibits explore the lives of neighborhood children, the

commitment of the residents who worked at Hull-House, artwork by Chicago

artists who trained and taught at Hull-House, historical photographs of the

neighborhood, and the restored bedroom of Jane Addams, where you can see her

1931 Nobel Peace Prize, the first ever given to an American woman.

But the real story of Hull-House lies in the thousands of

changed and transformed lives that passed through it. One exhibit

explores two of those lives: Hilda Satt Polachek and Jesús Torres.

Born in Poland , Polachek

immigrated to the United States

and Chicago

when just a little girl. At the age of 18, she began attending courses at

Hull-House and discovered a talent for writing. Her memoir of her time at

Hull-House, I Came a Stranger:

The Story of a Hull-House Girl, was published posthumously in 1989

and is one of the best windows into life inside a settlement house. A

Mexican migrant, Jesús Torres learned ceramics at the Hull-House Kilns,

receiving instruction from Russian immigrant artist Morris Topchevksy in the

1930s. Thanks to his Hull-House training, Torres became a successful and

widely admired ceramic artist, doing much work with Chicago ’s Carl Street Studios.

|

| The oldest known photograph of Hull-House. Photo courtesy of Jane Addams Hull-House Museum. |

|

| Hull-House at it looked in the 1920s. Photo courtesy of Jane Addams Hull-House Museum. |

Other Recommended

Sites: Many Mexicans came north in the 1920s, looking for work

at the Chicago

factories. They settled into

neighborhoods, bringing a vibrant culture and traditions with them. Fittingly, Chicago

is now home to the National Museum of Mexican Art located in Pilsen on the Lower West Side . The

museum showcases the beauty and richness of Mexican culture which has

flourished not just in the country of Mexico but throughout the Americas .

|

| A painting of Hull-House that served as a basis for the 1960s restoration. Image courtesy of Jane Addams Hull-House Museum. |

Tour America's History Itinerary

Thursday’s destination: Feehan Library, Mundelein Seminary

© 2013 Lee Price